Créé

-

on 9 November 2006 at the Opéra national de Paris (Paris National Opera House)

Musique

-

Alfred Schnittke

Chorégraphie

-

Thierry Malandain

Décor et costumes

-

Alain Lagarde

Conception lumières

-

Jean-Claude Asquié

Ballet

-

for 14 dancers

Durée

-

30 minutes

Note of intent

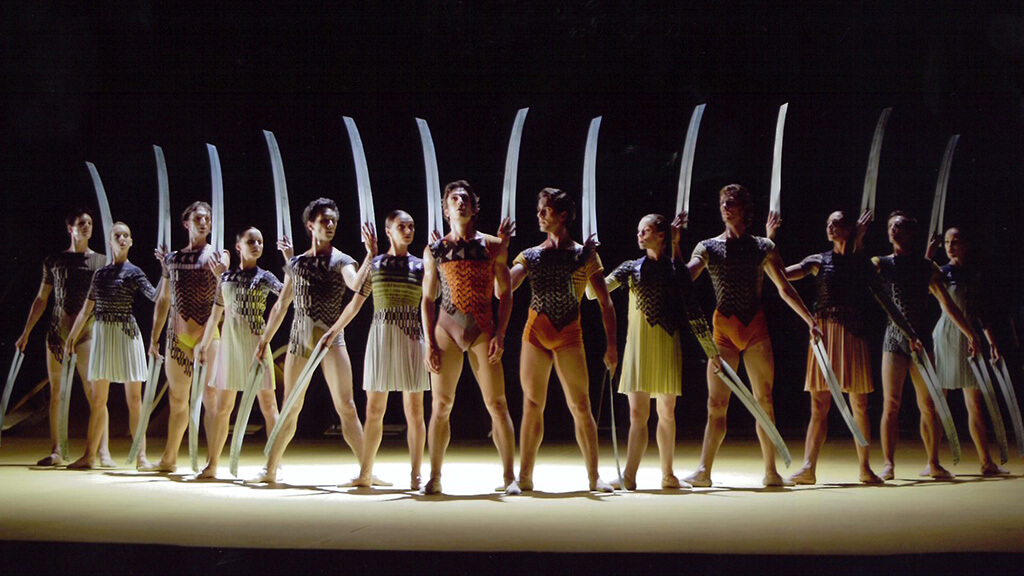

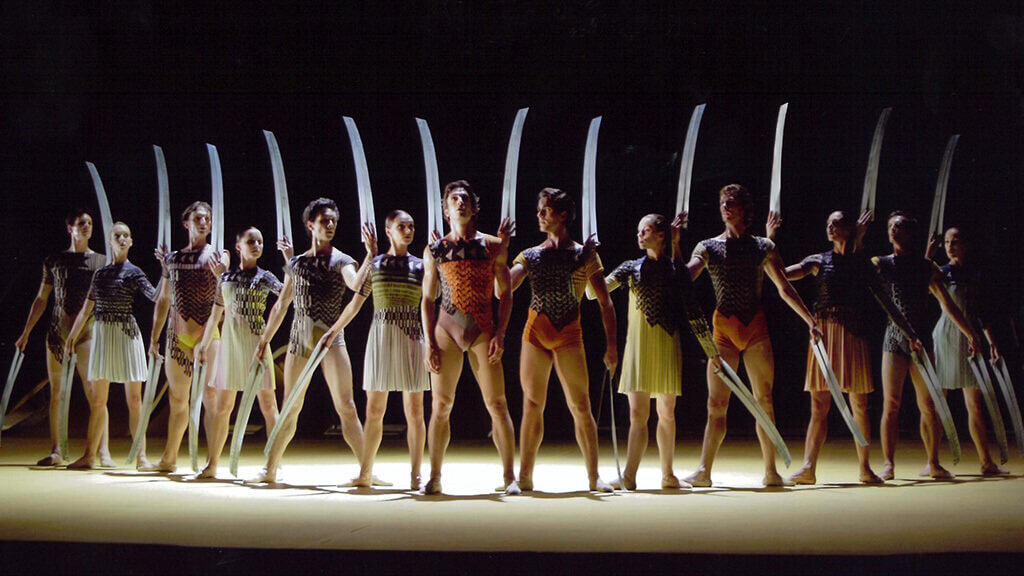

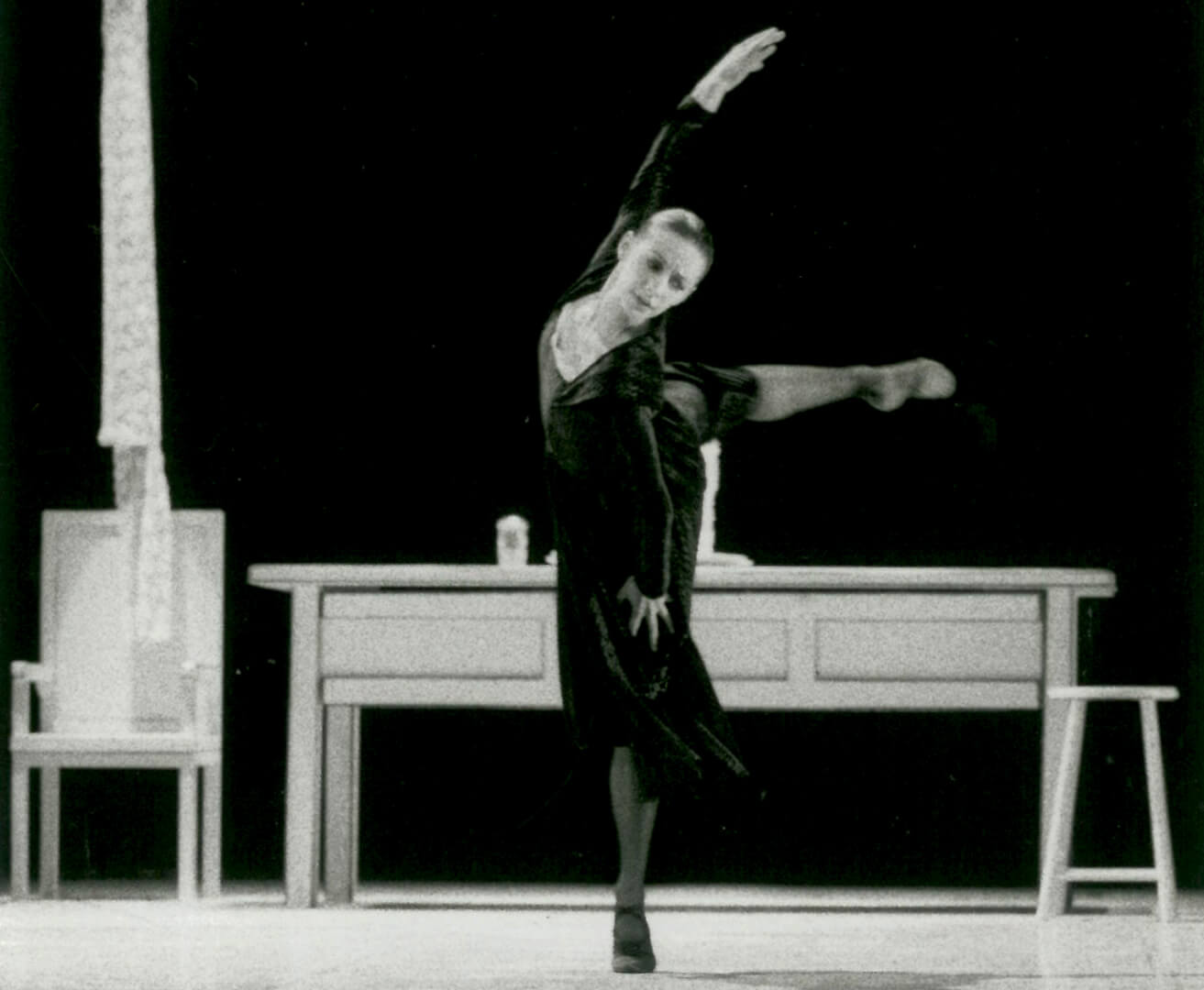

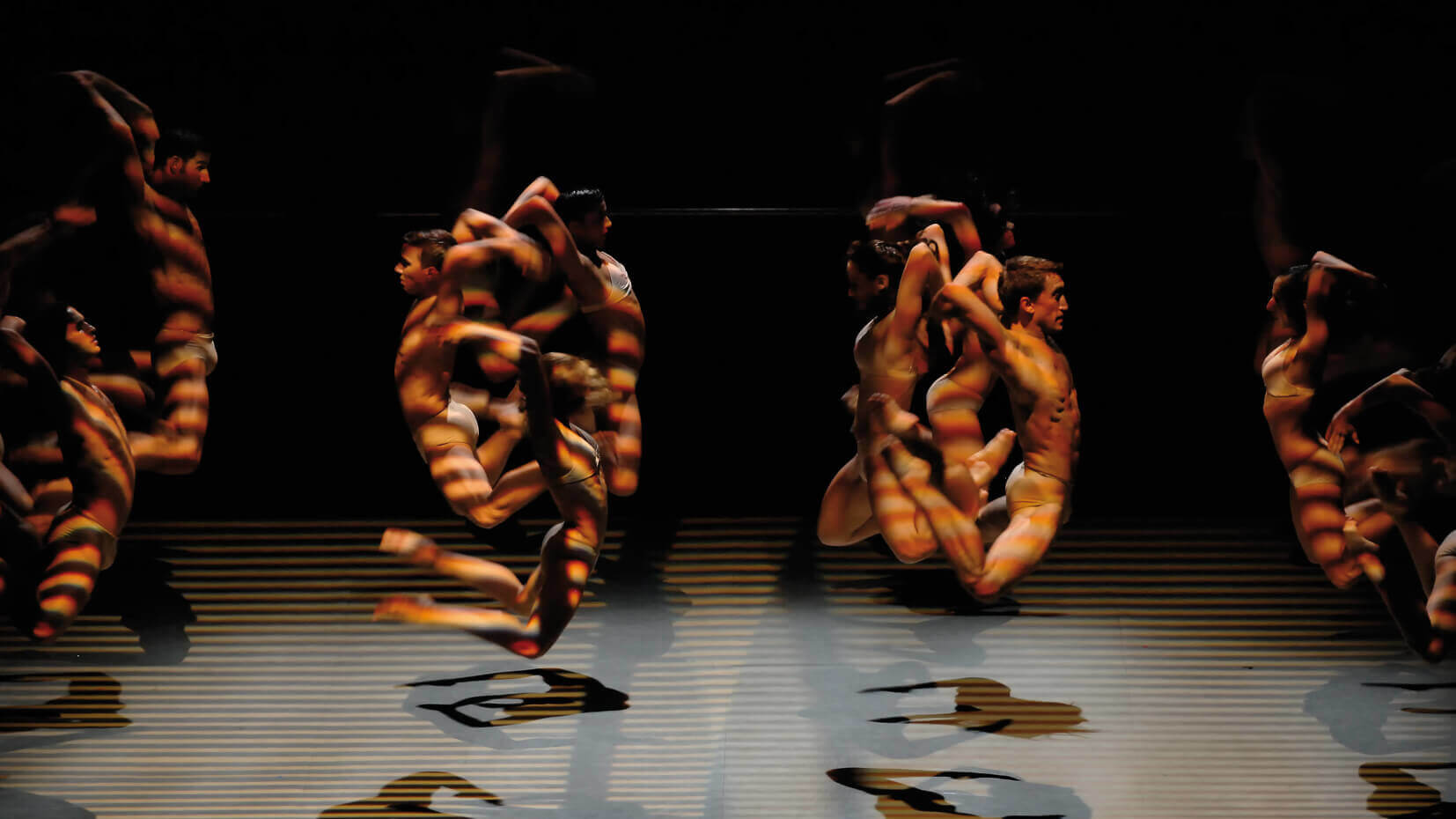

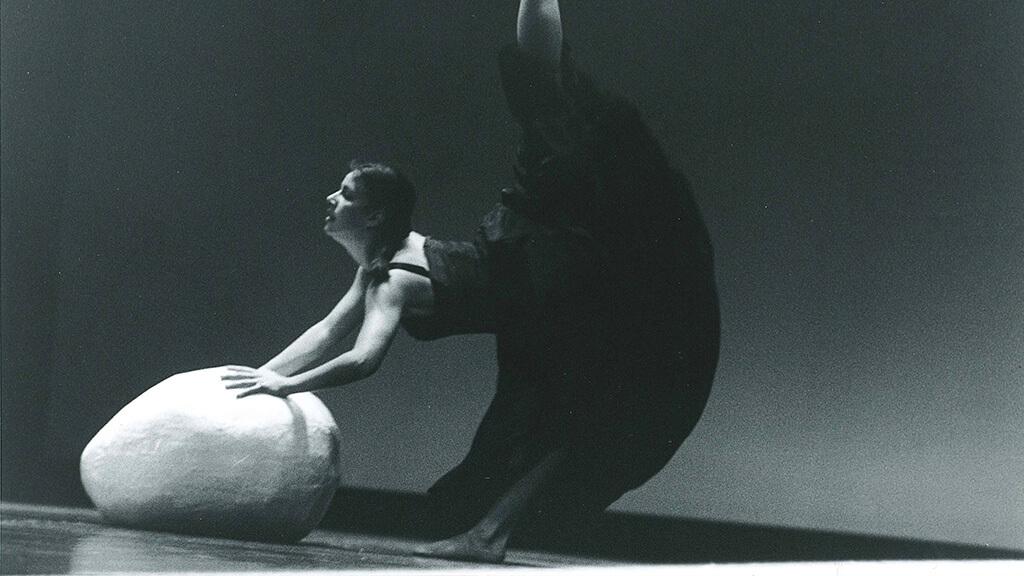

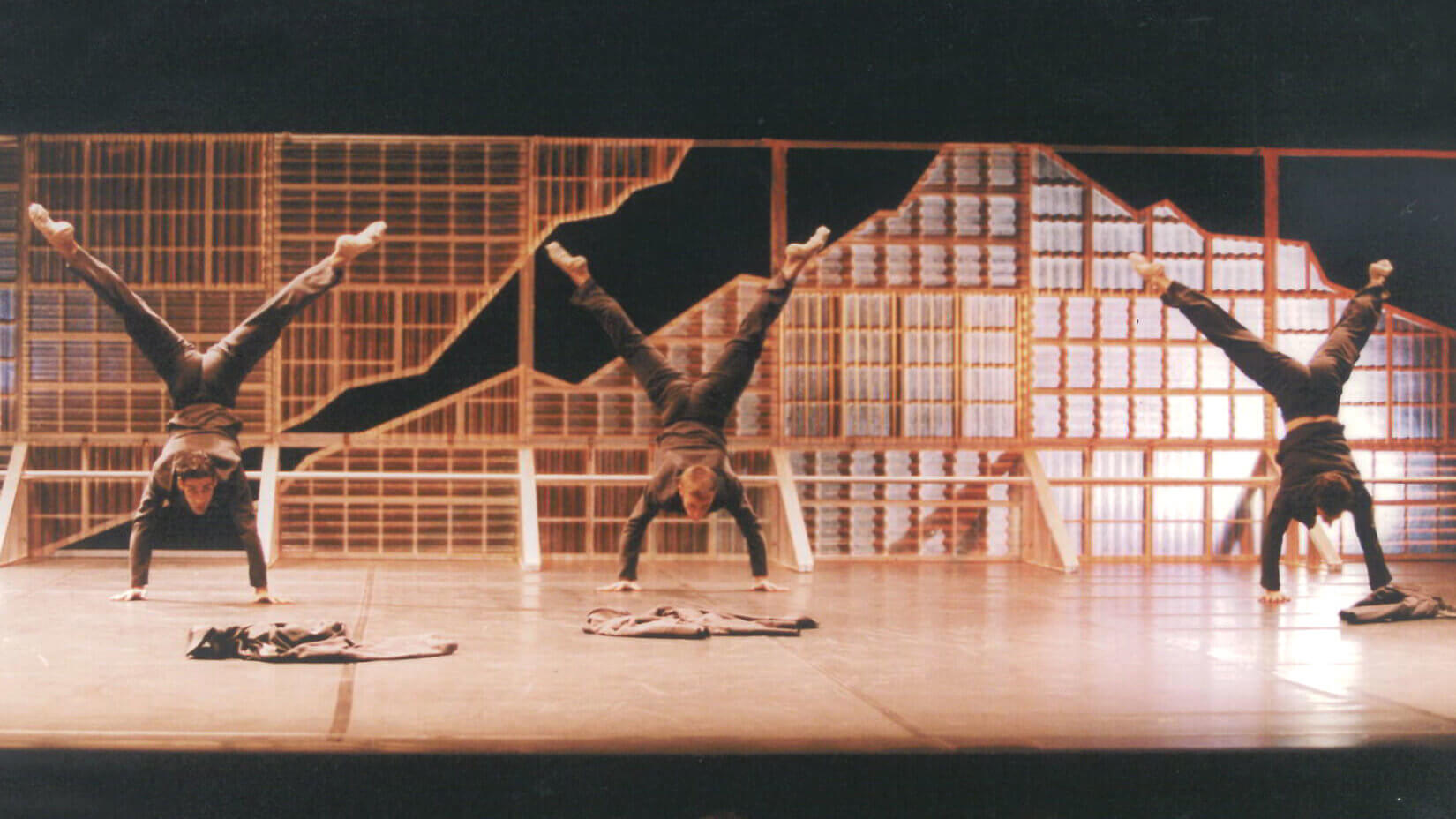

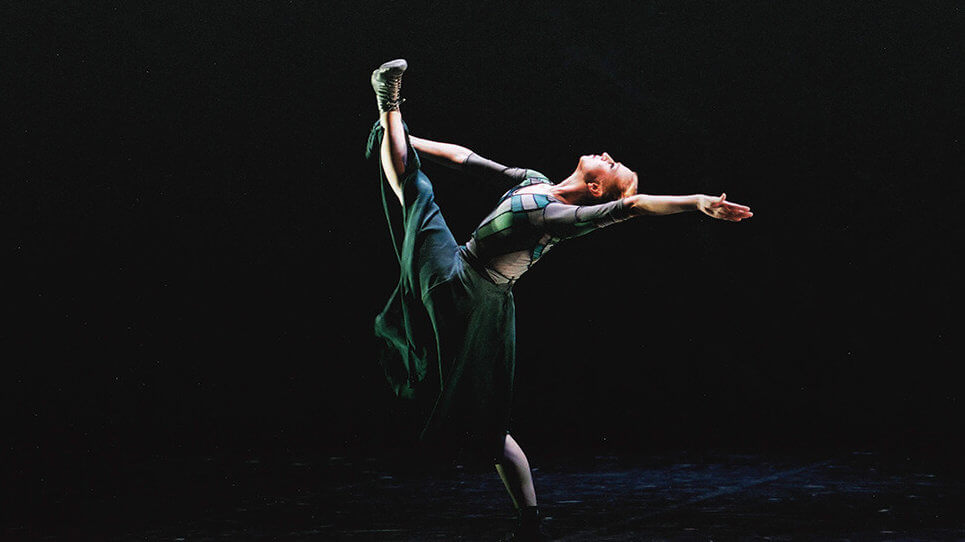

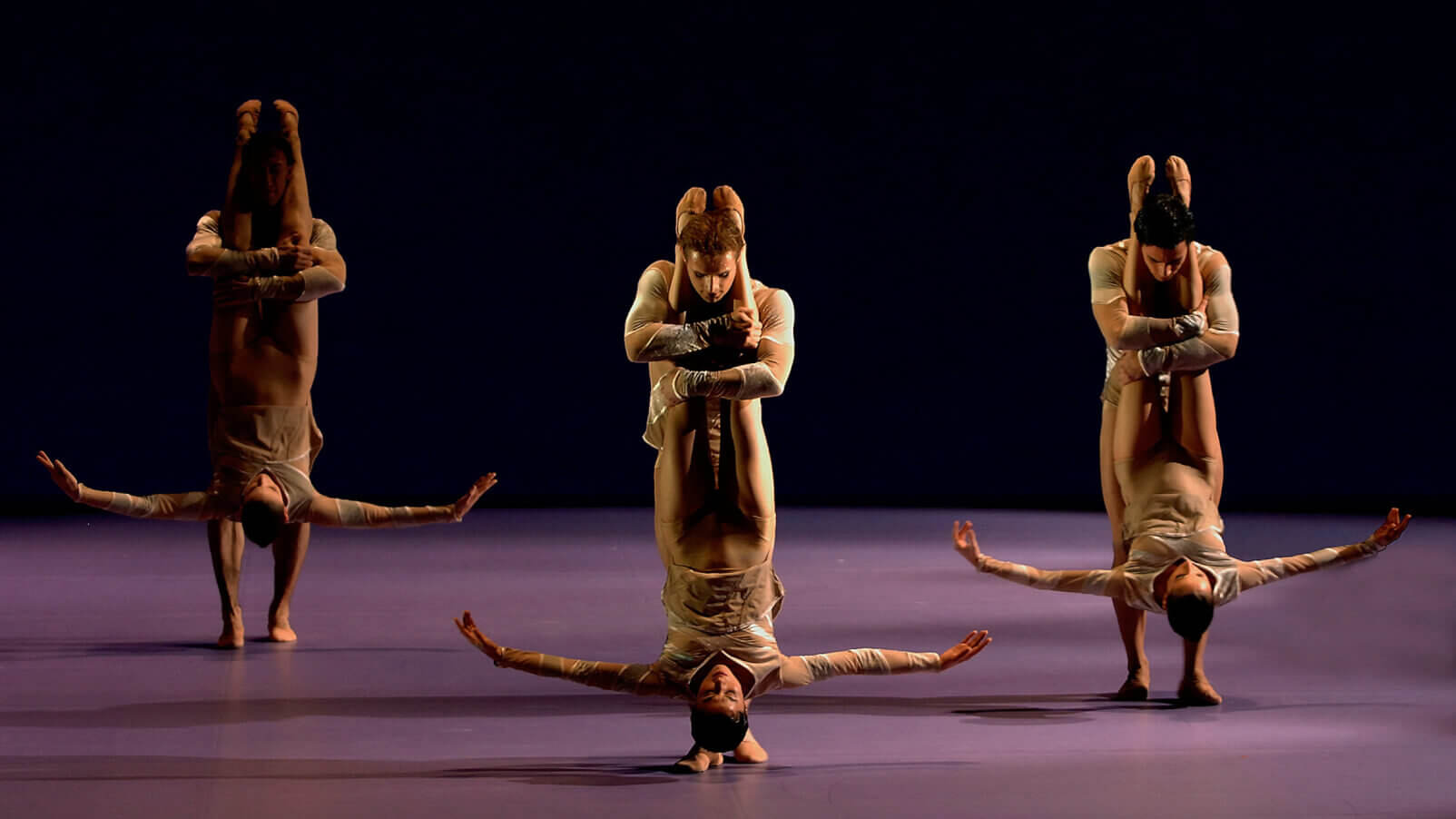

The ballet L’Envol d’Icare or The Flight of Icarus was created as part of a tribute to Serge Lifar and was performed with Suite en Blanc (1943) and Les Mirages (1947). By inviting men to not rise above human nature, the ancient moral of the myth of Icarus serves as a warning against hubris. However, Icarus is also symbolic of a human desire to defy gravity. We might accuse the teenager of disobeying or madly wanting to defy the Gods. But by flying too close to the sun, perhaps he simply wanted to admire it close up. At the beginning, there is a labyrinth, representing Man and his nature, but also a theatre in which Icarus, obscure in his own mind, goes towards the light. In this game, the Minotaur becomes his concealed inner monster - a Chimera that he must destroy to break with animalistic domination. By rebelling, he is Theseus, killing the creature to be free of it. Aided by Ariadne, the monster’s sister and the daughter of the “wide-shining” Pasiphaë, he manages to leave the labyrinth’s darkness to assert his radiant and holy side. Jacques Attali wrote, “All of the labyrinth parables tell this quadruple tale in one form or another - a journey, hardship, an initiation and resurrection”. The resurrection takes place here during the successive metamorphoses of the Minotaur, Theseus and Icarus. It’s the same dancer who leaves darkness and reaches the light. By his side, Ariadne, the daughter of the sun and moon by his side, unrolls the thread of this journey, adapted from ancient recollections. Thus fourteen dancers symbolize the number of tributes given to the Minotaur. Their dancing which weaves various movements together is a reminder of the crane dance, the forerunner of the farandole, reflecting the labyrinth’s twists and turns. And finally, to earn heaven’s favours on New Year’s Day in Palestine, a ritual ceremony would end with a winged man leaping into thin air, sacrificing himself for the benefit of all mankind. A ritual that we’ll turn upside down, as everyone will sacrifice themselves to fulfil the myth. Except for Icarus who is still alive.

Thierry Malandain

Press

More of a freestyle performance than a tribute, this short ballet is enchanting with sweeping and waving effects, and even a stylised game of feathers which turn into wings on Benjamin Pech’s shoulders. This illustrative effect is regrettable however when Malandain follows the music of Alfred Schnittke’s magnificent Concerto for Piano and Strings too closely ; though Lifar would’ve enjoyed this evening.Les Echos, Philippe Noisette • 16 October 2006

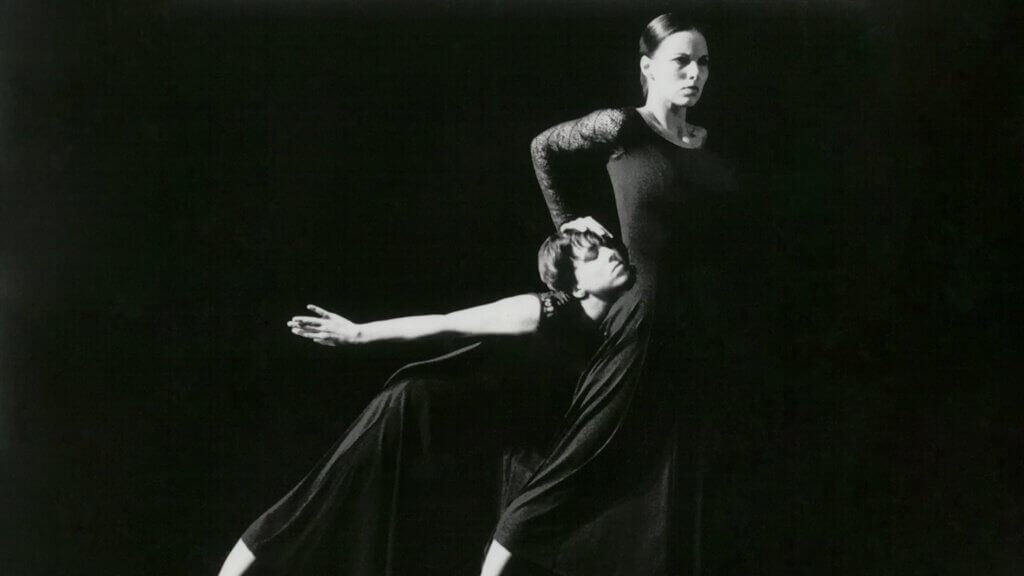

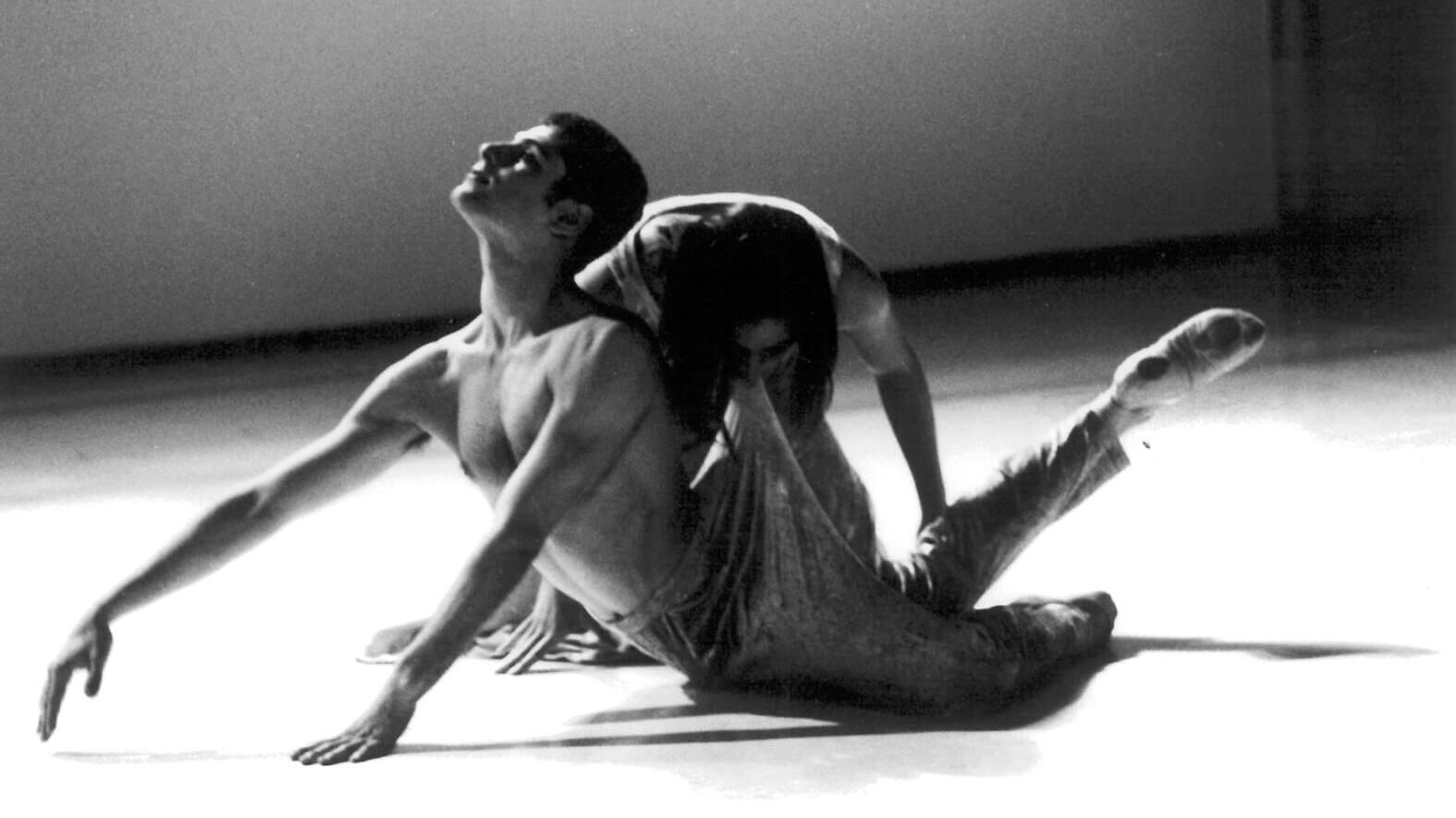

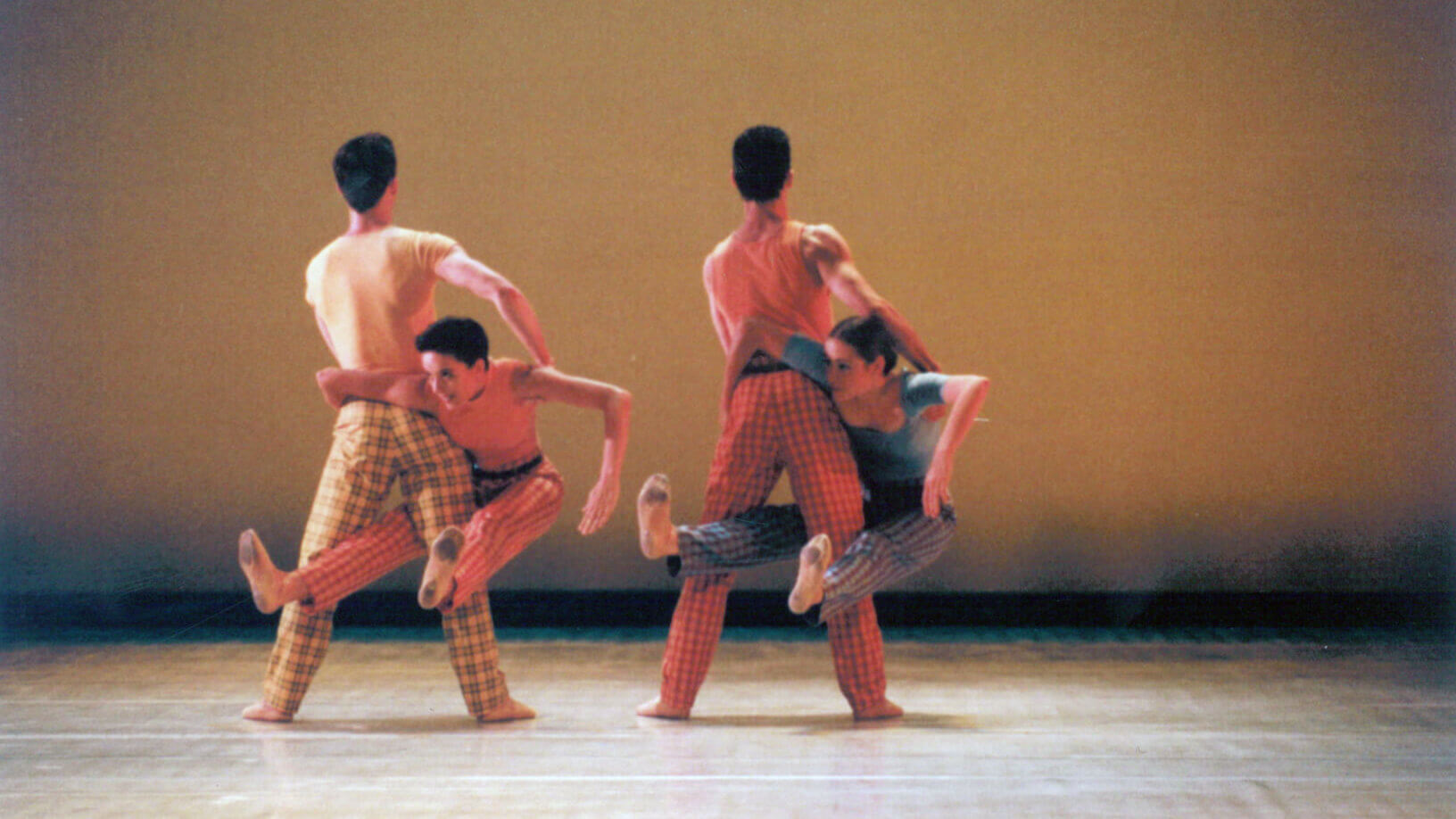

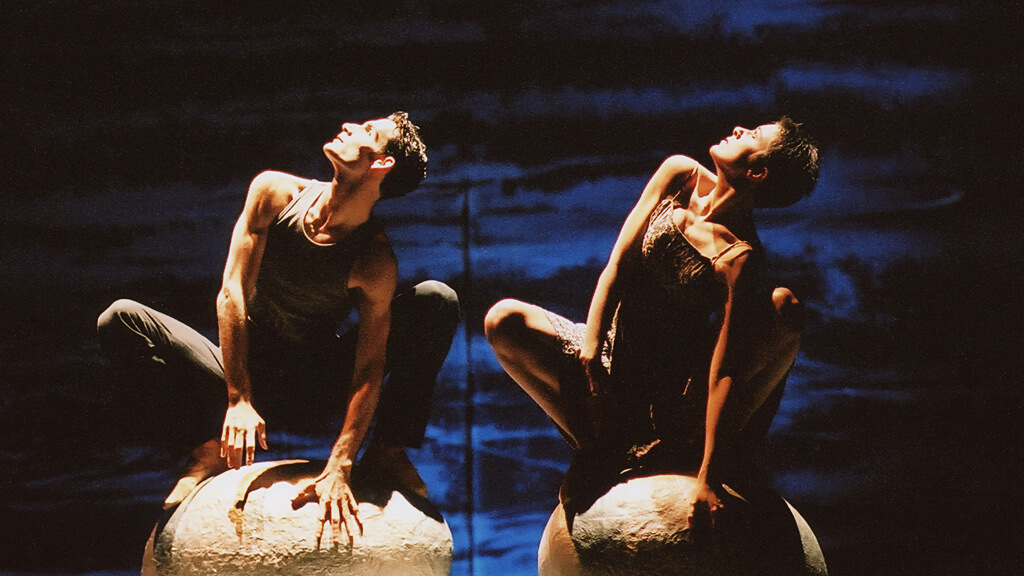

Then came L'Envol d'Icare, created by Thierry Malandain for the Opera’s dancers. The title and theme are a tip of the hat to Lifar’s Icarus but nothing more. As for the rest, one might be surprised by the theme of flight from a choreographer as eminently down to earth as Malandain. At the core of this ballet with primitive palpitations, a hero that’s part Daedalus, Icarus and Theseus is alternately absorbed or turned away by the group, an impulsive and overpowering circular dance; a sort of chosen one to put it simply, but who will find the passage to another place. The flight itself doesn’t take place, just enormous wings unfurling; gorgeous. Benjamin Pech, a handsome and touching chosen one, does not stand up on the tip of one of the remarkable diving boards designed by Alain Lagarde. He lies down, stomach and thighs pressed against the board like a heavy piece of meat on the butcher’s block. It’s this heaviness, this sensual gravity which is so appealing with Malandain, heavy arms, closed fists, and a rounded back. It’s both a simple and mysterious ballet, with no tricks and straightforward, which follows Schnittke’s score brilliantly - soothing, hammering, lyrical, disturbing, wonderfully elusive and perfectly fitting for this labyrinth. Mélanie Hurel’s beautiful rendition of Ariadne should be noted as well as Alain Lagarde’s amazing props and costumes. Should be seen again and again; a ballet that’s gaining ground.Altamusica.com, François Fargues • 17 October 2006

Thierry Malandain asserts his extremely personal style and writing with remarkable musical quality. He reinvents the solar myth with Benjamin Pech - which is his first performance as principal dancer - and impressive ensembles and farandoles.Le Figaro, Isabelle Danto • October 2006

Malandain ultimately choreographed his version of the myth of Icarus to the musical score of Russian-Volga German composer Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998), in this particular case, his Concerto for Piano and Strings, written in 1979. It’s a distinctly more optimistic version than the one told by the old moral because it has a happy end. By bringing together the emblematic figures of the Minotaur, Theseus and Icarus with one dancer, Thierry Malandain proposes a rite of passage leading to an actual resurrection, the flight of Icarus, the last incarnation which demonstrates Man’s “radiant and holy side”. By openly being a “classical aesthetic explorer”, Thierry Malandain breaks away from conventional codes via freedom and remarkably fluid agility. Playing a man walking towards the light, Benjamin Pech (principal dancer) embodies the role of the hero with incredible strength and vitality, giving each one of his faces the depth of spiritual metamorphosis. A splendid incarnation.Classictoulouse.com, Robert Pénavayre • 17 October 2006

Inspired more by the myth and its consequences than by the character himself, Thierry Malandain has created a coherent piece of work, with Mediterranean-style light that’s almost like the sea. We’re in Crete or any place where the sun is the central element. Not surprising since the nymph Pasiphaë was his daughter, right ? And didn’t Icarus die when his wings were burned by the sun? Subtler, his creation of circular dances, seemingly simple yet beautiful and polished writing, don’t they allude to the round dances which were the forerunners to choreography since time immemorial ? And what about this Icarus, multifaceted and changing, who dreams of flying or who wants to defy human nature - doesn’t he look like any other dancer ? Performed by a fine cast which brings together Benjamin Pech and Nolwenn Daniel, both equally charming and powerful, and accompanied by Alfred Schnittke’s Concerto for Piano and Strings, this Icarus is definitely Malandain taking flight.Danser, Agnès Izrine • November 2006

With L’Envol d’Icare, Thierry Malandain offers us a performance which alludes to the myth of the labyrinth without actually being narrative. He approaches his work as Serge Lifar’s worthy heir, through referent movements which typify dance. So for example, the Minotaur doesn’t have horns, but clenches his fists and thus gives meaning to his bodily states. Constantly searching for symbolism, Malandain wonderfully expresses emotion through dance and its culture, all why respecting Opera tradition. Well suited for this company of which the establishment’s influence can be felt in the work’s conception, this ballet, both musical and harmonious, nonetheless evokes innovating aesthetics, which is rarely seen in current contemporary creations; aesthetics in which one feels both filiation, as well as great freedom in adaptation. In this way, the choreographer uses the cohesion of the corps de ballet in the ensemble scenes to highlight the soloists Nolwenn Daniel and Benjamin Pech, whereas normally, the dancers of his company, with very different physiques and personalities, make him go in another direction in his creative process. The stage design contributes to the overall harmony, as well as the props, costumes, and lighting which serve the musical quality that’s so important to the choreographer.Danse,Jérôme Frilley • November 2006

In the second ballet, L'envol d'Icare, Thierry Malandain's first creation for the Paris Opera Ballet, the director of the "Centre Chorégraphique National" in Biarritz played around with his subject. Finding the music by J.E. Szyfer and Arthur Honegger used in Lifar's own 1935 ballet, Icare, somewhat dated, he substituted a score by Schnittke created for The Labyrinth, a ballet which tells the story of the seven young girls and seven youths sent from Athens to feed the Minotaur, that half-bull, half-human creature imprisoned in Crete by King Minos. Theseus, aided by the king's daughter and Dedale, the architect who built the maze, overcomes the bull, but Dedale is punished and shut in the maze with his son, Icarus. The work ends when Icarus, escaping from his prison with wings of wax, goes too close to the sun, melts them and goes crashing back to earth. “While my ballet springs from the tale of the Minotaur”, Malandain told me, “it's an abstract work with, for example, movements which recall the horns of the bull”. The French choreographer had already created a ballet some years ago, Les creatures, also inspired by Lifar's 1929 work, and his familiarity with the style of Les Ballets Russes as well as with the qualities of the Paris dancers was evident. He had also staged his personal versions of Bolero, Pulcinella, L'après-midi d'un faune, and Spectre de la rose successfully for his own company, and this new work was a harmonious ballet, ideally suited to the interpreters and the occasion. Malandain is a choreographer with a language of his own who can adapt it to the dancers he's working with, and while they initially did not have his style, they soon absorbed it, he told me. Jérémie Bélingard, a dancer with an untameable wild streak, was particularly well-cast as Theseus/Icarus.Culturekiosque.com, Patricia Boccadoro • 2d November 2006